Special Interest and Study Day report

Study Day Report: Chinese Imperial Court Costume and Insignia of Rank

Lecturer: David Rosier

Held on Tuesday October 23rd 2018 at Harpenden small public hall

The subject matter sounds serious and rather academic, but this study day was an exhilarating dash through Chinese imperial history, most specifically the Qing (pronounced ‘Ching’) dynasty, and the evolution of court dress.

The discovery of silk as far back as 4000 BC was the trigger that caused fabric to become the ultimate symbol of wealth and status. A regulatory system for court costumes developed from the third millennium BC onwards. From then on quasi-religious ceremonies were performed annually to ensure an adequate supply of mulberry tree leaves to feed the silk worms, so that the production of silk bolts would be sufficient to meet Imperial demand.

However, it wasn’t until the Qing dynasty (1644-1911 AD) that actual garments were preserved, leaving visual evidence for future generations. Previously there was documentary evidence, but the garments themselves had been buried with their owner, lost forever. The Emperor Qianlong (1735-1796) evolved the regulatory code to an extreme level. He produced 18 volumes and 5,000 pages of codification, with 6,000 hand-painted illustrations. Nothing was left to chance.

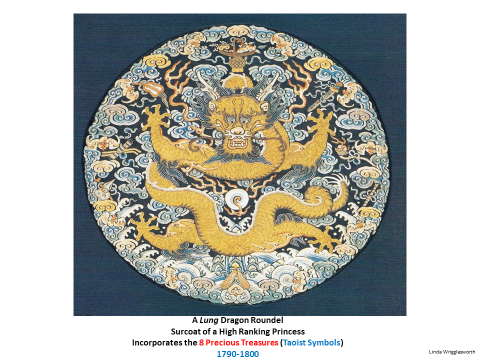

David guided us through the complex symbolism of the insignia. The dragon was the most important, a benevolent but powerful creature that represented the Emperor himself and could only be used by the imperial family. Use by lesser mortals was illegal and punishable by death.

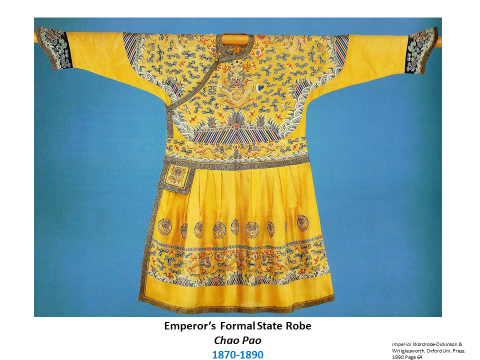

Colours too were regulated, yellow for example being the imperial colour, seen in the Emperor’s state robe below, upper image. The yellow state robe below, lower image, was exceptionally worn by the Empress if she appeared on her own in public. Her robe displays the phoenix, her emblematic bird.

The regulations also extended to military and bureaucratic ranks, and were as formalised as imperial insignia. Strange beasts represented specific ranks, like this paradise flycatcher:

:

9th Rank Civil Official: Paradise Flycatcher

We learnt about the prolonged and highly formalised process for entering military and civil service, through a series of examinations designed to reduce tens of thousands of applicants to just 300 successful candidates who would become court officials. Even the last 300 were carefully graded and their insignia awarded accordingly. The very top level were the ‘Mandarins’. Hence the term applied to our top civil servants in Britain.

That perhaps is enough to give a flavour of the importance and regulatory discipline of court dress. From 1776 Qianlong’s rule was weakened by corruption and a reluctance to trade with the West. He was succeeded in 1796 by a series of weak emperors and the observation of the code deteriorated. In 1911 the Empire itself failed, due to corruption, attacks by foreign powers and a failure to produce a reliable heir.

David brought his superb original collection of insignia to the study day, some examples illustrated above. We couldn’t touch, but we could see the beauty and complexity of the work produced by armies of skilled weavers and embroiderers centuries ago.

The cultural pleasures of the day were enhanced by a delicious and well organised coffee break and lunch provided by our special interest day organiser Susan Aldridge and her team of helpers.